IMPORTANT NOTE

12/01/2022

The content of this page was originally written in 2013, to coincide with Goodbye to Beekman Place's initial publication.

When I first posted this, I only had one novel written and had yet to understand the "totality" of the project, and it's eventual three-novel story arc of undiagnosed Dissociative Identity Disorder. Specifically, I didn't realize how my eleven different "alters" were using the book's visuals & characters to speak directly to the reader (in an effort to make the reader aware of their existence).

The following content assumed that Goodbye to Beekman Place was a "stand alone book," and was thus written as such.

I've decided to leave it "as is" for the moment, and will likely change it after When People Go Away is complete.

Please keep this in mind when reading.

- Sir Dave

Goodbye to Beekman Place

Information Page

Information Page

A Fourteen-Year Obsession

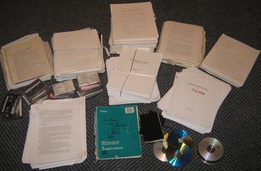

The many drafts of Goodbye to Beekman Place.

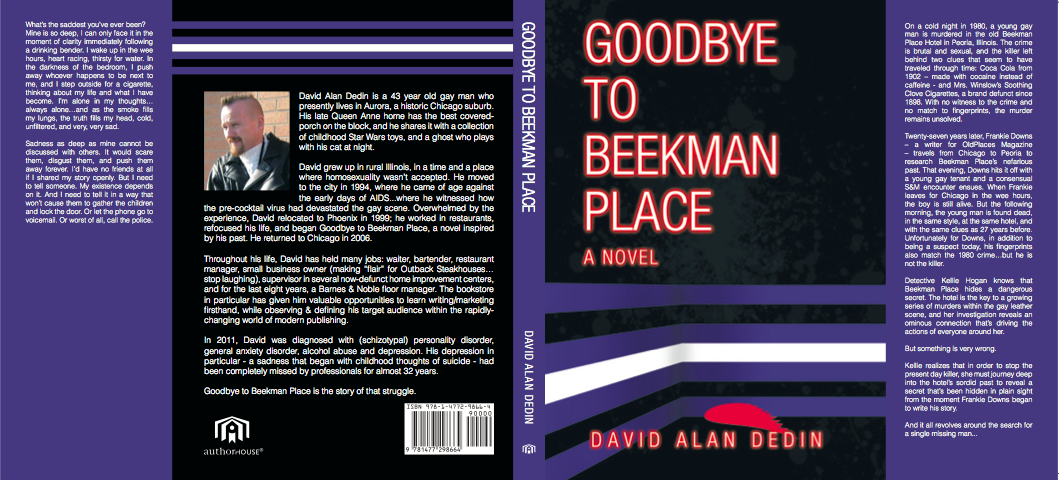

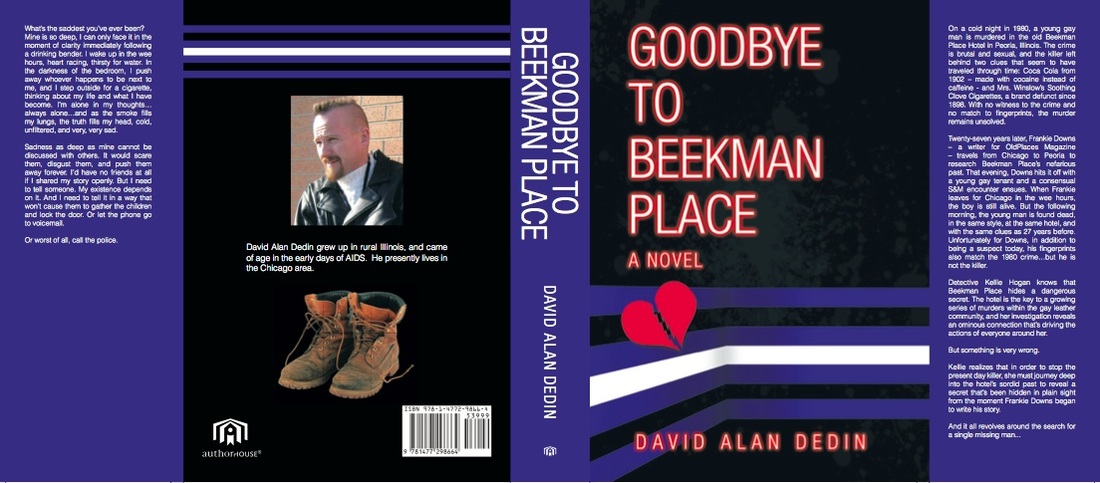

Goodbye to Beekman Place is my first novel. Its publication marks the end of a 14 year writing project, and it's one of those books that can't be easily described by a few short paragraphs inside a dust jacket.

The project walks a fine line between psychological mystery and personal memoir. I believe that the story of how the book was written is even more important than the novel's plot, and I sincerely believe that Goodbye to Beekman Place can be read as a case study of undiagnosed schizotypal personality disorder.

The story as a whole is a metaphor for the chaos that happens within the schizotypal mind in crisis - and how hard it is to face depression. With that in mind, here is my original Author's Note, which was shortened dramatically for publication:

The project walks a fine line between psychological mystery and personal memoir. I believe that the story of how the book was written is even more important than the novel's plot, and I sincerely believe that Goodbye to Beekman Place can be read as a case study of undiagnosed schizotypal personality disorder.

The story as a whole is a metaphor for the chaos that happens within the schizotypal mind in crisis - and how hard it is to face depression. With that in mind, here is my original Author's Note, which was shortened dramatically for publication:

Author's Note:

The Wall of Televisions

Suicide must be done sober, or else you'll be dismissed as a drunk; but as drinking was the only way I could turn off the wall of televisions. Type A hereditary alcoholism was indeed, a double-edged sword.

Goodbye to Beekman Place took me fourteen years to write, and the book – quite literally - put me in the loony bin. In 2011, after waking from drinking myself to sleep the night before, I calmly got up, made coffee, took a shower…and asked a neighbor to drive me to the hospital. The following week was spent within the Central DuPage Hospital Crisis Intervention Unit, where I was diagnosed with (schizotypal) personality disorder, general anxiety disorder, alcohol abuse, and depression -

My depression in particular – a sadness that began with a childhood thoughts of suicide in 1980 - had been completely missed by professionals for almost 32 years.

Schizotypal Personality Disorder is a mild, high-functioning form of schizophrenia…and in my opinion, extremely similar to autism. It’s a condition that I’ve learned isn’t fully understood by psychiatrists…and it’s only “mild” in the sense that people like myself are able to keep jobs, maintain (guarded) familial/friendship relationships, and for the most part, “hide in plain sight.” SPD is a mood disorder, characterized by the need for social isolation. It’s existence is controversial, and has not yet been recognized in the World Health Organization’s ICD-10; but SPD is acknowledged by the American Psychiatric Association – and included in the DSM-IV-TR. Personally though, when it comes to explaining symptoms to those unfamiliar, I think the Mayo Clinic says it best:

• Incorrect interpretation of events, including feeling that external events have personal meaning

• Peculiar thinking, beliefs or behavior

• Belief in special powers, such as telepathy

• Perceptual alterations, in some cases bodily illusions, including phantom pains or other distortions in the sense of touch

• Idiosyncratic speech, such as loose or vague patterns of speaking or tendency to go off on tangents

• Suspicious or paranoid ideas

• Flat emotions or inappropriate emotional responses

• Lack of close friends outside of the immediate family

• Persistent and excessive social anxiety that doesn't abate with time

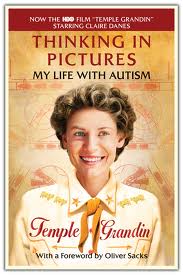

When Temple Grandin first told the world “I think in pictures,” it revolutionized our understanding of autism. Grandin gave everyone – from professionals to laymen - a tangible point of reference with a single, easy-to-understand sentence: “I think…in pictures." With those four words, the doors to autism/Aspergers suddenly blew open, and sufferers who had literally been “trapped in their heads” were finally able to connect with the world around them. Since then, Grandin has reached thousands of people with books, blogs, and public appearances; her story has not only revolutionized the understanding/treatment of the spectrum, but autism itself has gone “mainstream.”

Goodbye to Beekman Place took me fourteen years to write, and the book – quite literally - put me in the loony bin. In 2011, after waking from drinking myself to sleep the night before, I calmly got up, made coffee, took a shower…and asked a neighbor to drive me to the hospital. The following week was spent within the Central DuPage Hospital Crisis Intervention Unit, where I was diagnosed with (schizotypal) personality disorder, general anxiety disorder, alcohol abuse, and depression -

My depression in particular – a sadness that began with a childhood thoughts of suicide in 1980 - had been completely missed by professionals for almost 32 years.

Schizotypal Personality Disorder is a mild, high-functioning form of schizophrenia…and in my opinion, extremely similar to autism. It’s a condition that I’ve learned isn’t fully understood by psychiatrists…and it’s only “mild” in the sense that people like myself are able to keep jobs, maintain (guarded) familial/friendship relationships, and for the most part, “hide in plain sight.” SPD is a mood disorder, characterized by the need for social isolation. It’s existence is controversial, and has not yet been recognized in the World Health Organization’s ICD-10; but SPD is acknowledged by the American Psychiatric Association – and included in the DSM-IV-TR. Personally though, when it comes to explaining symptoms to those unfamiliar, I think the Mayo Clinic says it best:

• Incorrect interpretation of events, including feeling that external events have personal meaning

• Peculiar thinking, beliefs or behavior

• Belief in special powers, such as telepathy

• Perceptual alterations, in some cases bodily illusions, including phantom pains or other distortions in the sense of touch

• Idiosyncratic speech, such as loose or vague patterns of speaking or tendency to go off on tangents

• Suspicious or paranoid ideas

• Flat emotions or inappropriate emotional responses

• Lack of close friends outside of the immediate family

• Persistent and excessive social anxiety that doesn't abate with time

When Temple Grandin first told the world “I think in pictures,” it revolutionized our understanding of autism. Grandin gave everyone – from professionals to laymen - a tangible point of reference with a single, easy-to-understand sentence: “I think…in pictures." With those four words, the doors to autism/Aspergers suddenly blew open, and sufferers who had literally been “trapped in their heads” were finally able to connect with the world around them. Since then, Grandin has reached thousands of people with books, blogs, and public appearances; her story has not only revolutionized the understanding/treatment of the spectrum, but autism itself has gone “mainstream.”

New Years Day 2010 was the morning that I first saw the HBO film "Thinking in Pictures: The Temple Grandin Story;" I remember being so moved by it’s visuals, I could barely talk when the movie ended – something I later learned was SPD anxiety. After years of struggling for words in shrinks’ offices, I finally had a point of reference of my own; “I think in pictures, too! Just like in the movie!” But as my own psychiatric issue was still undiagnosed at the time, it would take another year-and-a-half, before I spoke my own simple sentence: “I think in...visual metaphors.”

And to this day, I fear that no one understands just how important that sentence is.

* * * * *

The Visual Metaphors of the Schizotypal Mind

For the sake of brevity, it would be impractical to explain SPD traits item-by-item within this Author’s Note; the Mayo Clinic symptoms are easy to understand, and I ask you to keep them in mind – and to reference them as needed.

But as a reader, in order to enjoy Goodbye to Beekman Place, it’s important I describe my own SPD thought-process, so you can recognize that process in action, and understand how it motivated the development of this story. And it’s really quite a simple concept, no different than watching a show like Mad Men, where the actors are having a conversation in the foreground, while something far more important happens in the back.

With that in mind, here’s how I think:

I think in “metaphors,” rather than “clear ideas.” I have an uncontrollable need to find “patterns” in behaviors & events – and I search for those patterns’ hidden motives & meanings. I believe there are no coincidences, and that an omnipresent force is watching me (like a Christian’s view of God); I believe that force occasionally sends me messages through news headlines, songs on the radio, and patterns in events…and I use those messages to help make decisions within daily life.

Because of these issues – all of which I now understand to be traits of SPD – I frequently compare people & events to books, movies, and television – as well as memories from my past; it’s how I find a common “point of reference” to make myself clear when talking to other people, and most just dismiss me as a movie-buff, or a guy who’s a little eccentric. If you’re a fan of the TV show Community, please think of the character Abed.

And to this day, I fear that no one understands just how important that sentence is.

* * * * *

The Visual Metaphors of the Schizotypal Mind

For the sake of brevity, it would be impractical to explain SPD traits item-by-item within this Author’s Note; the Mayo Clinic symptoms are easy to understand, and I ask you to keep them in mind – and to reference them as needed.

But as a reader, in order to enjoy Goodbye to Beekman Place, it’s important I describe my own SPD thought-process, so you can recognize that process in action, and understand how it motivated the development of this story. And it’s really quite a simple concept, no different than watching a show like Mad Men, where the actors are having a conversation in the foreground, while something far more important happens in the back.

With that in mind, here’s how I think:

I think in “metaphors,” rather than “clear ideas.” I have an uncontrollable need to find “patterns” in behaviors & events – and I search for those patterns’ hidden motives & meanings. I believe there are no coincidences, and that an omnipresent force is watching me (like a Christian’s view of God); I believe that force occasionally sends me messages through news headlines, songs on the radio, and patterns in events…and I use those messages to help make decisions within daily life.

Because of these issues – all of which I now understand to be traits of SPD – I frequently compare people & events to books, movies, and television – as well as memories from my past; it’s how I find a common “point of reference” to make myself clear when talking to other people, and most just dismiss me as a movie-buff, or a guy who’s a little eccentric. If you’re a fan of the TV show Community, please think of the character Abed.

When I think, I can literally “see” computers. I see lights and keyboards and systems status gauges. I see flat-screen monitors and busy, NASA-like workstations. I literally see people at work – characters from television, movies, and books – and all are wearing “work” uniforms of various themes, from Starfleet jumpsuits to business shirts & ties. This is actually happening at this moment, as I write. The whole process takes the context of a Star Trek bridge, with stations devoted to navigation (a metaphor for daily life), communication (speaking/behaving correctly for situations), defense (for when SPD symptoms flare up/cause problems), life support (my physical/emotional well-being), and other smaller stations that appear as needed. 90% of the time, the stations work seamlessly together; they network, email, share files, and direct intelligence to the “Captain” - a single individual who coordinates final decisions. (Please note: I am not describing a multiple personality situation; this is all just a visual metaphor, a proven coping technique that I’ve used since childhood.)

Just like The Enterprise, my bridge is constructed around a large, multi-functional, constantly changing view-screen. During the decision process, that screen becomes a wall of televisions – with each TV showing a different video (from movies/TV), a past memory (real and/or perceived), or a “suggested course of action” (in regards to what I’m experiencing that moment). At any given moment, I’m bombarded with hundreds of visual images/metaphors, and envisioning this bridge is how I keep my thoughts focused, avoiding SPD tangents.

Despite its chaotic nature, this process is completely normal to me; most of the time, it’s near instantaneous – and undetectable to others. Where thinking becomes difficult, however – where my bridge buckles under the information’s volume – is any situation that involves heavy “emotion,” especially since SPD tends toward incorrect interpretation of events and paranoia.

Most of daily life, I control my emotions by imagining computer firewalls – or “playing a character” (again, like Abed from Community). But heavy emotions confuse me – like dealing with angry coworkers, or consoling a person in need. And in my effort to hold on to a human connection, my wall of televisions inevitably plays scenes/memories of previous emotional confusion, showing example after example of similar situations. And please keep in mind, that’s all against the background of unavoidable SPD symptoms, which, more often than not, only make things worse –

It’s literally like using a slow computer.

The single most frustrating (and maddening) SPD trait for me is that the televisions rarely show “clear examples” of the present issue; they display different visual metaphors whose intent must be interpreted like dreams, with hidden meanings that aren’t easily seen on the surface. And this is further complicated by the fact that many “dreams” were inspired by real-life moments/memories. My visual memory is near-photographic, and no matter how old a memory, it’s as real to me as though it happened yesterday.

Think about that. It’s like Billy Pilgrim from Slaughterhouse Five.

When I think, I literally cannot let go of the past, and for those who don’t understand SPD, talking to me grows difficult, and at times a little scary. I constantly bring up past events, in an effort to find a common point of reference: “What’s happening now is just like what happened then,” etc. It’s a trait that often backfires, making me seem meek, indecisive, or petty. And it’s worse during relationships, as the wall of televisions makes me jump to conclusions, turning innocent misunderstandings into sudden fights, creating frustration & anger –

Please think of Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver.

Despite its chaotic nature, this process is completely normal to me; most of the time, it’s near instantaneous – and undetectable to others. Where thinking becomes difficult, however – where my bridge buckles under the information’s volume – is any situation that involves heavy “emotion,” especially since SPD tends toward incorrect interpretation of events and paranoia.

Most of daily life, I control my emotions by imagining computer firewalls – or “playing a character” (again, like Abed from Community). But heavy emotions confuse me – like dealing with angry coworkers, or consoling a person in need. And in my effort to hold on to a human connection, my wall of televisions inevitably plays scenes/memories of previous emotional confusion, showing example after example of similar situations. And please keep in mind, that’s all against the background of unavoidable SPD symptoms, which, more often than not, only make things worse –

It’s literally like using a slow computer.

The single most frustrating (and maddening) SPD trait for me is that the televisions rarely show “clear examples” of the present issue; they display different visual metaphors whose intent must be interpreted like dreams, with hidden meanings that aren’t easily seen on the surface. And this is further complicated by the fact that many “dreams” were inspired by real-life moments/memories. My visual memory is near-photographic, and no matter how old a memory, it’s as real to me as though it happened yesterday.

Think about that. It’s like Billy Pilgrim from Slaughterhouse Five.

When I think, I literally cannot let go of the past, and for those who don’t understand SPD, talking to me grows difficult, and at times a little scary. I constantly bring up past events, in an effort to find a common point of reference: “What’s happening now is just like what happened then,” etc. It’s a trait that often backfires, making me seem meek, indecisive, or petty. And it’s worse during relationships, as the wall of televisions makes me jump to conclusions, turning innocent misunderstandings into sudden fights, creating frustration & anger –

Please think of Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver.

Finally, I talk to myself – and it takes a conscious effort to stop. I talk to myself at home, at work, in the car, in the shower…anytime I have a private moment; and as you might imagine, it can scare the hell out of people.

When I talk, I rehearse conversations, practicing like an actor who’s learning his lines. I run through every scenario – “What if the conversation goes this way? What might have happened had I said this instead?” Talking to myself is how I control the SPD trait: Idiosyncratic speech, such as loose or vague patterns or the tendency to go off on tangents, and the older I get, the better it works – as the bridge now has a lifetime of memories to reference.

But the dark side to this behavior is that it makes others uncomfortable, which creates a Catch 22: I talk to myself to practice communication, but the act itself makes others avoid me. So, the solution is bittersweet: when frustrated, I say nothing at all. And silence in itself isolates me further, exacerbating SPD paranoia…and adding fuel to loneliness. As you read Goodbye to Beekman Place, please pay close attention to references to “silence” and the phrase, “Shh, No Talking.”

When I talk, I rehearse conversations, practicing like an actor who’s learning his lines. I run through every scenario – “What if the conversation goes this way? What might have happened had I said this instead?” Talking to myself is how I control the SPD trait: Idiosyncratic speech, such as loose or vague patterns or the tendency to go off on tangents, and the older I get, the better it works – as the bridge now has a lifetime of memories to reference.

But the dark side to this behavior is that it makes others uncomfortable, which creates a Catch 22: I talk to myself to practice communication, but the act itself makes others avoid me. So, the solution is bittersweet: when frustrated, I say nothing at all. And silence in itself isolates me further, exacerbating SPD paranoia…and adding fuel to loneliness. As you read Goodbye to Beekman Place, please pay close attention to references to “silence” and the phrase, “Shh, No Talking.”

“My name is David, and I’m an alcoholic,” is the only thing I’ve ever said within an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. Specifically, when it comes to sharing addiction with a group, I’ve never made it past AA’s opening prayers - this line in particular: "There are those too who suffer from grave emotional and mental disorders, but many of them do recover if they have the capacity to be honest…”

I’ve been a drinker since my 21st birthday, and the progression of addiction over the last two decades reads as a textbook example of alcoholism – with a pattern of tolerance, denial, and growing dependence. Goodbye to Beekman Place was written during this period, typically in the mornings after an evening bender, and always early, hung over, and when I was able to write without self-delusion.

As I wrote this book, I didn’t begin with an outline or synopsis; I felt nothing more than an urgency to write something, like a manic crafting a suicide note, apologizing for past behaviors. The wall of televisions in particular, showed me interconnected scenes that I knew had to happen in the story. I knew the book had to open with Prohibition, and I knew that the plot had to involve an old hotel named “Beekman Place.”

And the story always started the same:

In 1980, in Peoria Illinois, a young gay man is murdered, and his body is found within the old Beekman Place hotel. The murder is brutal & sexual, and the killer left behind two unexplainable clues: 1, Coca-Cola made with cocaine (rather than caffeine), bottled in 1902, as fresh as though it had been made today; and 2, “Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Clove Cigarettes,” a brand defunct since 1898, also impossibly fresh. There are no witnesses, no fingerprints. The murder is never solved…

I knew that the characters had to reveal my most guarded secrets – far beyond just surface issues like addiction & social anxiety, and far more personal than just basing fictional characters on people from my past. I also knew that the story’s ultimate subject matter would be uncomfortable for most to read, causing them to put the book down before reaching the end.

So it was important that I hook the reader with a popular writing format…and who doesn’t love a good murder mystery?

Twenty-five years later, Frankie Downs – 40 years old, gay, a writer for Old Places magazine – travels from Chicago to Peoria, to write a story on Beekman Place, a Prohibition-era hotel with a storied past. A functional alcoholic, Frankie is already buzzed when he meets Libby, the hotel’s owner since 1980; over the next several hours, Frankie tours the building with Libby, who insists that they drink “to get in the hotel’s spirit.” They start inside the “Janitor’s Closet” (a hidden basement speakeasy), where Libby explains that Beekman Place was built by Bill Roanoke, an openly-gay man who inherited his father’s whiskey fortune 100 years ago. The hotel’s history proves as bizarre as Libby herself, and Frankie seems particularly interested by the phrase “Shh…No Talking,” emblazoned on the lobby’s elevator.

Later that evening, Frankie meets a young gay tenant, who recognizes him from a fetish website. A consensual S&M encounter ensues, and the tenant is still alive when Frankie leaves the building (staggering drunk) in the wee hours…but the next day, that tenant is found murdered: same brutality, same clues, and a witness who saw Frankie leave the building. To make matters worse, Frankie’s fingerprints also match the 1980 murder…but he is not the killer. Of course, everyone expects “denial” from a drunk…

Every word and every scene had to be perfect – not in an arrogant writer’s way, but in the sense that the scenes themselves were allowing a larger story to be told…hidden in plain sight, within the scenes’ visual metaphors:

1. Beekman Place was built during “Prohibition,” a time when drinking was not allowed…or in other words, an alcoholic’s sobriety.

2. The end of Prohibition marked the beginning of “The Great Depression,” or more specifically, the loneliness of (undiagnosed) Schizotypal Personality Disorder in adulthood.

3. Old Coke & old cigarettes – as fresh as though they were made yesterday – are metaphors for “schizotypal memory,” and how the past can seem as real as the present.

4. “Frankie” is short for “Frankenstein,” the monster of alcoholism. His guilt is a metaphor not just for addiction’s denial, but the cause of a lifelong “great depression” that had grown dangerous in recent years…

I’ve been a drinker since my 21st birthday, and the progression of addiction over the last two decades reads as a textbook example of alcoholism – with a pattern of tolerance, denial, and growing dependence. Goodbye to Beekman Place was written during this period, typically in the mornings after an evening bender, and always early, hung over, and when I was able to write without self-delusion.

As I wrote this book, I didn’t begin with an outline or synopsis; I felt nothing more than an urgency to write something, like a manic crafting a suicide note, apologizing for past behaviors. The wall of televisions in particular, showed me interconnected scenes that I knew had to happen in the story. I knew the book had to open with Prohibition, and I knew that the plot had to involve an old hotel named “Beekman Place.”

And the story always started the same:

In 1980, in Peoria Illinois, a young gay man is murdered, and his body is found within the old Beekman Place hotel. The murder is brutal & sexual, and the killer left behind two unexplainable clues: 1, Coca-Cola made with cocaine (rather than caffeine), bottled in 1902, as fresh as though it had been made today; and 2, “Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Clove Cigarettes,” a brand defunct since 1898, also impossibly fresh. There are no witnesses, no fingerprints. The murder is never solved…

I knew that the characters had to reveal my most guarded secrets – far beyond just surface issues like addiction & social anxiety, and far more personal than just basing fictional characters on people from my past. I also knew that the story’s ultimate subject matter would be uncomfortable for most to read, causing them to put the book down before reaching the end.

So it was important that I hook the reader with a popular writing format…and who doesn’t love a good murder mystery?

Twenty-five years later, Frankie Downs – 40 years old, gay, a writer for Old Places magazine – travels from Chicago to Peoria, to write a story on Beekman Place, a Prohibition-era hotel with a storied past. A functional alcoholic, Frankie is already buzzed when he meets Libby, the hotel’s owner since 1980; over the next several hours, Frankie tours the building with Libby, who insists that they drink “to get in the hotel’s spirit.” They start inside the “Janitor’s Closet” (a hidden basement speakeasy), where Libby explains that Beekman Place was built by Bill Roanoke, an openly-gay man who inherited his father’s whiskey fortune 100 years ago. The hotel’s history proves as bizarre as Libby herself, and Frankie seems particularly interested by the phrase “Shh…No Talking,” emblazoned on the lobby’s elevator.

Later that evening, Frankie meets a young gay tenant, who recognizes him from a fetish website. A consensual S&M encounter ensues, and the tenant is still alive when Frankie leaves the building (staggering drunk) in the wee hours…but the next day, that tenant is found murdered: same brutality, same clues, and a witness who saw Frankie leave the building. To make matters worse, Frankie’s fingerprints also match the 1980 murder…but he is not the killer. Of course, everyone expects “denial” from a drunk…

Every word and every scene had to be perfect – not in an arrogant writer’s way, but in the sense that the scenes themselves were allowing a larger story to be told…hidden in plain sight, within the scenes’ visual metaphors:

1. Beekman Place was built during “Prohibition,” a time when drinking was not allowed…or in other words, an alcoholic’s sobriety.

2. The end of Prohibition marked the beginning of “The Great Depression,” or more specifically, the loneliness of (undiagnosed) Schizotypal Personality Disorder in adulthood.

3. Old Coke & old cigarettes – as fresh as though they were made yesterday – are metaphors for “schizotypal memory,” and how the past can seem as real as the present.

4. “Frankie” is short for “Frankenstein,” the monster of alcoholism. His guilt is a metaphor not just for addiction’s denial, but the cause of a lifelong “great depression” that had grown dangerous in recent years…

I knew that the plot required an ensemble-cast of interconnected characters, with each person carrying a clue to the overall story. I knew the book had to read like a “soap opera” - especially within the first 200 pages, before a sudden change of setting – and I knew that every character shared connections that complicated the lives of those around. While writing I often thought of DALLAS, my favorite show as a kid.

Some characters are drunks. Some fight depression. Some carry the shame that they’ve hidden since childhood, and they battle that issue in their effort to appear as functional as possible. Some characters are detectives. One is a sexual predator. And all characters display textbook traits of SPD, struggling to balance the worlds within their heads against their sober realities.

With that in mind, I also knew that the story required “patterns,” with many visual metaphors repeated again & again…particularly images of looking through glass, and references to rain and/or water in a bathroom shower. Those patterns continued within the characters’ behaviors, with repeated phrases of dialogue, and manners of movement intended to mirror stagecraft – as though a director was giving instruction from behind the forth wall.

Most of all, I knew the story couldn’t be “linear,” in exactly the same way as the TV show Lost (which I didn’t see until years after the novel’s completion). Goodbye to Beekman Place had to be told from multiple points of view…and in hindsight now, I realize that by doing so, I literally showed the reader what happens within the schizotypal mind when a life-threatening problem must be solved…

…And that problem could be seen in glaring first-person statements that spoke directly to the reader, begging them to look closer at the story – and to see the crisis that I could not myself, hidden in plain sight, literally, in the novel’s very center: "I want to kill myself.” Goodbye to Beekman Place was a “cry for help” from a man dying of loneliness.

Hold that thought.

Some characters are drunks. Some fight depression. Some carry the shame that they’ve hidden since childhood, and they battle that issue in their effort to appear as functional as possible. Some characters are detectives. One is a sexual predator. And all characters display textbook traits of SPD, struggling to balance the worlds within their heads against their sober realities.

With that in mind, I also knew that the story required “patterns,” with many visual metaphors repeated again & again…particularly images of looking through glass, and references to rain and/or water in a bathroom shower. Those patterns continued within the characters’ behaviors, with repeated phrases of dialogue, and manners of movement intended to mirror stagecraft – as though a director was giving instruction from behind the forth wall.

Most of all, I knew the story couldn’t be “linear,” in exactly the same way as the TV show Lost (which I didn’t see until years after the novel’s completion). Goodbye to Beekman Place had to be told from multiple points of view…and in hindsight now, I realize that by doing so, I literally showed the reader what happens within the schizotypal mind when a life-threatening problem must be solved…

…And that problem could be seen in glaring first-person statements that spoke directly to the reader, begging them to look closer at the story – and to see the crisis that I could not myself, hidden in plain sight, literally, in the novel’s very center: "I want to kill myself.” Goodbye to Beekman Place was a “cry for help” from a man dying of loneliness.

Hold that thought.

THE BIG PICTURE

Radio World is a Prohibition-themed amusement park, and the setting for this novel’s ultimate conflict. It’s a world of imagination, as though Disney built Manhattan, and it’s streets are filled with lights, heat, TV screens, and people – all metaphors for a lifetime of experiences, as real today as they were in the past. And it’s a city that’s kept as secret as a Speakeasy, accessible only to “members” who adhere to strict rules of conduct, encapsulated in the phrase: “Shh, No Talking!” The park is accessible through the Beekman Place elevators, though only if a new member has met their sponsor’s requirements.

But something has gone terribly wrong. An unforeseen event has shaken Radio World to its core, in the same way as 9-11 brought New York to a standstill. The city is in crisis, and for the first time in history, Radio World must face the grief that caused its very existence…for if left unchecked, will most certainly cause its demise. And it’s a secret as clear as a headline, hidden in plain sight within the story’s visual metaphors.

…and it all revolves around the search for a single, missing man.

END OF AUTHOR'S NOTE

Radio World is a Prohibition-themed amusement park, and the setting for this novel’s ultimate conflict. It’s a world of imagination, as though Disney built Manhattan, and it’s streets are filled with lights, heat, TV screens, and people – all metaphors for a lifetime of experiences, as real today as they were in the past. And it’s a city that’s kept as secret as a Speakeasy, accessible only to “members” who adhere to strict rules of conduct, encapsulated in the phrase: “Shh, No Talking!” The park is accessible through the Beekman Place elevators, though only if a new member has met their sponsor’s requirements.

But something has gone terribly wrong. An unforeseen event has shaken Radio World to its core, in the same way as 9-11 brought New York to a standstill. The city is in crisis, and for the first time in history, Radio World must face the grief that caused its very existence…for if left unchecked, will most certainly cause its demise. And it’s a secret as clear as a headline, hidden in plain sight within the story’s visual metaphors.

…and it all revolves around the search for a single, missing man.

END OF AUTHOR'S NOTE

Multiple Points-of-View and First-Person Narration

From the earliest drafts of Goodbye to Beekman Place, readers have voiced strong opinions regarding the novel's atypical use of first-person narration (within a story that's predominantly told in third-person). Some readers quickly "got it," while others found it distracting…and as a writer, finding a common middle ground was indeed, an editing challenge.

Within the book, each chapter opens with a first-person monologue that speaks directly to the reader. In Part One of the book, these narratives bring up topics that are immediately covered within the following chapter - easy to follow. But as the novel processes into Parts Two & Three, these monologues intentionally take on a life of their own, and begin to share their own personal story - separate from what's happening in the book. When read by themselves - back to back, in order - the overall plot of the narratives mirrors the "frame story" of Frankie Downs and the Beekman Place murders. Both Frankie's story and the narrative's story are designed to lure the reader deeper into the book - a metaphor for "SHH, NO TALKING." And the lure itself is a metaphor for the omnipresent narrator's own fear of telling the reader too-much, too-soon - representing what it's like to live with guilt and shame.

See for yourself. The file below contains all chapter narratives, back to back, in order:

Within the book, each chapter opens with a first-person monologue that speaks directly to the reader. In Part One of the book, these narratives bring up topics that are immediately covered within the following chapter - easy to follow. But as the novel processes into Parts Two & Three, these monologues intentionally take on a life of their own, and begin to share their own personal story - separate from what's happening in the book. When read by themselves - back to back, in order - the overall plot of the narratives mirrors the "frame story" of Frankie Downs and the Beekman Place murders. Both Frankie's story and the narrative's story are designed to lure the reader deeper into the book - a metaphor for "SHH, NO TALKING." And the lure itself is a metaphor for the omnipresent narrator's own fear of telling the reader too-much, too-soon - representing what it's like to live with guilt and shame.

See for yourself. The file below contains all chapter narratives, back to back, in order:

| narratives.docx | |

| File Size: | 174 kb |

| File Type: | docx |

After reading the chapter narratives, you might also be interested in the original chapter narratives…the ones included in the rough draft of Goodbye to Beekman Place, before the project was edited. Note how I viewed the story at the time, before I understood how my brain was trying to "talk through" schizotypal anxiety. At my editor's request, most of the later narratives were rewritten for clarity and story relevance. Still, they're an interesting read:

| monologues.doc | |

| File Size: | 90 kb |

| File Type: | doc |

All of these narratives - both old & new - are the voice of an omnipresent narrator who is heard throughout the story. That narrator's voice is crucial. It's the story-within-the-story, held in bondage by "SHH, NO TALKING." And to understand how that narrator communicates is the key to understanding - and enjoying -Goodbye to Beekman Place.

That topic is covered within the segment below.

That topic is covered within the segment below.

Metafiction, Psychodrama, and Breaking the Fourth Wall

As mentioned in the Author's Note, Goodbye to Beekman Place was written over a turbulent 14-year period - a time in my life marked by alcoholism, loneliness, depression, and crippling SPD anxiety. In hindsight now, I was afraid to share the novel's real intent at the beginning, so I lured the reader with a "familiar" murder-mystery in hopes that they'd keep on reading once events progressed from Chicago to Radio World.

I'm aware that certain people could grow frustrated by the book's complicated nature, and I know that frustration leads to putting the book down before the end. But there's irony in that. Goodbye to Beekman Place's metafictional style engages the reader in "a story that must never reach an end"...so by frustrating the reader, the story is allowed to continue - and the omnipresent narrator keeps his impending suicide a secret.

But the reader misses the point if they fall victim to this distraction, as the written story is ultimately irrelevant when compared to the visual story that's been "hidden in plain sight" from the novel's very beginning:

I'm aware that certain people could grow frustrated by the book's complicated nature, and I know that frustration leads to putting the book down before the end. But there's irony in that. Goodbye to Beekman Place's metafictional style engages the reader in "a story that must never reach an end"...so by frustrating the reader, the story is allowed to continue - and the omnipresent narrator keeps his impending suicide a secret.

But the reader misses the point if they fall victim to this distraction, as the written story is ultimately irrelevant when compared to the visual story that's been "hidden in plain sight" from the novel's very beginning: